When Saint Constantine the Great moved the capital of the Roman Empire in the provincial but well positioned city of Byzantium‚ his aspiration was not only to transfer the power of Rome to the East but also to overshadow the eternal city with monuments of architecture that will find no rivalry in the world. Miraculously converted to Christianity‚ Constantine took the small city on the Bosphorus and built it from the ground into a Christian capital‚ erecting not idolatric temples but Christian churches with an architecture that no one has seen before.

The first Church commissioned by Constantine still stands today‚ Agia Irene‚ the Church of Holy Peace. The Church of the Holy Apostles‚ the burial place of Constantine that he did not see finished‚ the greatest church of its times‚ crowned the hills of Constantinople‚ watching impassibly the rise and fall of the great city‚ until 1461 when was demolished and turned into a mosque.

Following in the footsteps of Constantine‚ emperor Justinian continued the architectural trend of the new capital and in 537 inaugurated the greatest and the most iconic church of the Byzantium Period: Agia Sophia‚ the Church of the Holy Wisdom.

The Byzantine Style.

As the golden times of Empire started to dwindle down so did the size of the monuments that evolved from the great churches of Constantine and Justinian closer to a human scale. The new style‚ that started to emerged in the 7th to the 9th century continued to spread throughout the Orthodox East and the master builders of Byzantium became legendary for their craftsmanship and the exquisite beauty of their work.

Before we delve more into their work is important to recall that Byzantine church architecture did not serve a purpose in itself‚ was never a search for world greatness‚ but always aimed to serve a higher resolve. The churches of Byzantium were not monuments dedicated to their founders but houses of the Lord first‚ places of worship and antechambers of the Kingdom. Byzantine architecture is not art per se but serves a liturgical end. All its defining elements‚ beyond being structural or decorative‚ play a role in the fullness and richness of the Orthodox prayer life.

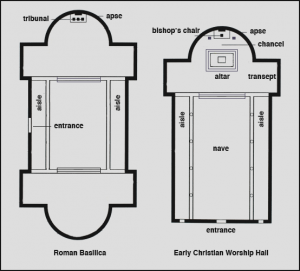

The early churches borrowed their architecture from the former Roman forum with a simple nave and a circular apse for the altar (the basilica style). Most of the churches followed a tri-cameral floor plan with an entrance area called narthex‚ reserved for the uninitiated‚ a main central worshipping area called naos or nave and a circular apse at the Eastern apex‚ bema or altar‚ the place were the Eucharistic Sacrifice was offered by the ordained Bishops and Priests. Some churches featured also an exo-narthex‚ a covered‚ vaulted canopy flanked by columns that extended the narthex frontward.

The early churches borrowed their architecture from the former Roman forum with a simple nave and a circular apse for the altar (the basilica style). Most of the churches followed a tri-cameral floor plan with an entrance area called narthex‚ reserved for the uninitiated‚ a main central worshipping area called naos or nave and a circular apse at the Eastern apex‚ bema or altar‚ the place were the Eucharistic Sacrifice was offered by the ordained Bishops and Priests. Some churches featured also an exo-narthex‚ a covered‚ vaulted canopy flanked by columns that extended the narthex frontward.

The tri-cameral layout of the Orthodox Church symbolically represents the journey of mankind from Creation to the Second coming of Christ. The narthex represents mankind from Creation until the coming of Christ; the naos is the world in the Christian era‚ while the altar represents the promised Kingdom. As one enters the church‚ passing from one liturgical space into the other‚ one becomes a personal participant in the journey of mankind towards salvation and transfiguration in Christ.

This rather simple layout progressively matured into much more intricate structures. The progress was on one hand owed to the ongoing refinement of the liturgical life itself that forced the architecture to develop with it‚ but also to the purposeful incorporation of major faith symbols in it’s spaces and shapes.

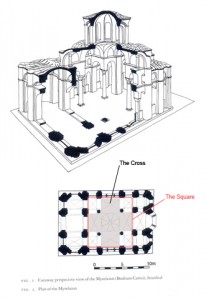

The cross was one of the earliest symbols incorporated‚ due to the centrality of the cross in Christian worship. Although there was great diversity in the Byzantine architecture‚ the cross-in-square plan became early on the flagship and the majority of churches from the 9th century on follow this design.

The cross-in-the-square plan generally features a central dome resting of four pillars‚ connected with four rectangular bays (usually barrel-vaulted) that constitute the arms of the cross. The Eastern arm ends in the altar apse while the Western goes to form the nave. The side arms were later extended outward‚ starting on Mount Athos in the 11th century‚ and each eventually received an apse meant to provide the acoustical amplification needed for the two choirs that typically serve in an Orthodox Monastery.

The cross-in-the-square plan generally features a central dome resting of four pillars‚ connected with four rectangular bays (usually barrel-vaulted) that constitute the arms of the cross. The Eastern arm ends in the altar apse while the Western goes to form the nave. The side arms were later extended outward‚ starting on Mount Athos in the 11th century‚ and each eventually received an apse meant to provide the acoustical amplification needed for the two choirs that typically serve in an Orthodox Monastery.

The simple description of the cross plan does not do justice to this type of churches however. The cross-in-square blossoms spatially from the play of volumes that places the dome in the center of the liturgical space‚ from where Jesus Christ Pantokrator‚ is blessing the whole creation. At the base of the dome the pendentives (the spherical triangles resulting from the intersection of spaces) represent the four corners of the world that the four Evangelists (depicted of them) have travelled to spread the Gospel. All curves of the apses‚ vaults and groins remind us of the nurturing protection of the Mother of God.

Materials

The exterior materials typically employed by the Byzantine builders generally focused on brick combined with stone. The inside was adorned with the most precious of materials: marble‚ gold‚ semi-precious gems‚ intricate woodcarvings‚ mosaics and iconography covering all the walls. No resources were spared for the glory of God. Even in harshest times the churches continued to be adorned as the Church expresses the richness of the promise Kingdom in material terms that people understand here and now.

The New Church

The Church in which you find yourself today tries to follow in the footsteps of the great master builders of the past. Although the parish did not have access to the materials nor the resources of the Roman Emperors‚ the new church fuses the Spirit of Byzantium with a number of modern and more affordable building techniques resolving to achieve in the end the Byzantine look and feel.

The Church in which you find yourself today tries to follow in the footsteps of the great master builders of the past. Although the parish did not have access to the materials nor the resources of the Roman Emperors‚ the new church fuses the Spirit of Byzantium with a number of modern and more affordable building techniques resolving to achieve in the end the Byzantine look and feel.

The church dedicated to St. John the Baptist‚ features a cross-in-square plan with a 30 ft diameter dome‚ resting on four columns and rising 65ft above the ground. The altar apse prolongs eastward and connects with two lateral rooms for liturgical usage. The nave unfolds to the West in a barrel-vaulted shape‚ flanked by two lateral groin-vaulted colonnades. Two lateral apses extend from dome North and South providing the natural acoustic surfaces needed for the services.

The barrel-vaulted narthex is separated from the nave by a door and opens outside into a generous exo-narthex that embraces the front and the two sides of the church‚ providing shelter from the Texas sun. Over the narthex the space also accommodates a choir loft with a barrel-vaulted ceiling that continues from the nave. A bell tower keeps vigil over the south side and is adorned with a small copper dome and a cross.

The church was erected using a core metal structure complimented by a more flexible and affordable wood supra-structure allowing the construction of the complicated arches‚ apses‚ vaults and pendantives that define the Byzantine architectural style.

The outside was finished using a combination of brick and stone woven in patterns characteristic to the traditional craftsmanship of the Byzantine era. The cascading angles of the roof are covered with metal sheets while the great dome and the bell tower received handcrafted copper coverings‚ which underline their architectural importance.

The outside was finished using a combination of brick and stone woven in patterns characteristic to the traditional craftsmanship of the Byzantine era. The cascading angles of the roof are covered with metal sheets while the great dome and the bell tower received handcrafted copper coverings‚ which underline their architectural importance.

The interior walls were completed keeping in mind the iconography that will adorn them in their entirety at one point. The dry wall was covered with fiberglass mesh‚ several layers of lime cement plaster and silicate paint that will ensure a proper surface for the future murals. The travertine based church floor is laid out in a Venetian pattern with inserts of different colors and sizes accentuating the architectural elements.

The altar stands three steps higher than the level of the nave emphasizing the upward trend our spiritual lives should have as we try to reach the Kingdom.  The altar iconostasis‚ built out of two-toned carved stone and intricate mosaic patterns‚ follows the typical Orthodox design with two royal doors in the center and two deacon doors on the sides. The iconostasis will host a total of ten 6ft tall icons‚ hand painted on wood‚ using the traditional egg-tempera technique. The placement of the icons follows the Church canons‚ with Christ and the Theotokos flanking the royal doors‚ archangels guarding the deacon doors and other saints ensuing on both sides.

The altar iconostasis‚ built out of two-toned carved stone and intricate mosaic patterns‚ follows the typical Orthodox design with two royal doors in the center and two deacon doors on the sides. The iconostasis will host a total of ten 6ft tall icons‚ hand painted on wood‚ using the traditional egg-tempera technique. The placement of the icons follows the Church canons‚ with Christ and the Theotokos flanking the royal doors‚ archangels guarding the deacon doors and other saints ensuing on both sides.

The two lateral apses are furnished with the traditional seating of the Orthodox churches‚ stasidia‚ high monastic chairs with intricate woodcarvings featuring Orthodox symbols like the Byzantine double-headed eagle‚ etc. The nave hosts twelve rows of wooden pews‚ a less traditional addition to the Orthodox Church space that has grown in popularity in the recent decades. On the solea‚ a bishop throne‚ manufactured from the same stone material‚ will compliment the iconostasis.

The two lateral apses are furnished with the traditional seating of the Orthodox churches‚ stasidia‚ high monastic chairs with intricate woodcarvings featuring Orthodox symbols like the Byzantine double-headed eagle‚ etc. The nave hosts twelve rows of wooden pews‚ a less traditional addition to the Orthodox Church space that has grown in popularity in the recent decades. On the solea‚ a bishop throne‚ manufactured from the same stone material‚ will compliment the iconostasis.

Today’s Masters

As the churches of the past owed their beauty to their master builders‚ so today we owe the beauty of our new church to the new master architects and builders that have used their knowledge of the past and have adapted it to the present‚ creating a magnificent structure that will host the future of our parish. Praise to you new master builders; you have made your ancestors proud!

By Fr. Vasile Tudora and Presbytera Mirela Tudora

Photos by Fr. Vasile Tudora and Vladimir Grygorenko

In The Footsteps Of The Old Masters Of Byzantium‚

Thank you for featuring our new church on your website!

http://www.orthodoxartsjournal.org/st-john-the-baptist-euless-texas/

Should read ‘your ancestors‚’ not ‘you ancestors.’

Thank you! 🙂